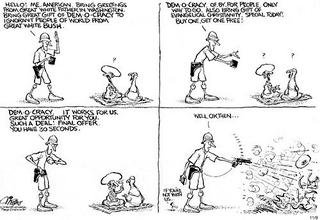

IT WAS indeed an "important" speech that US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice made in Cairo on Monday emphasising the need for democratic reforms in the Middle East. But it only served to emphasise the selective American vision as to who should do what and how in the region and the double standards that the US has always followed when dealing with this region.

Rice told the region's leaders not to fear their people's free choice — a great idea and concept of course. But she also used the forum to single out Egypt, Syria and Iran as countries which should transform themselves.

We all know that there are major shortcomings in the Egyptian political system, and it would take time before politicians entrenched in the corridors of power would accept the inevitability of change. There would a lot of political fireworks before the system would be open for circles other than the ruling party. The Egyptians are dealing with it, and, sooner or later, there will be changes in Egypt, but the US would not be able to impose them except in a peripheral context. The Egyptians themselves will have to take care of them.

In Syria, we have seen that the regime of Bashar Al Assad has taken serious steps towards reforms.

Assad is following a skilful political approach: He wants his people to see tangible and positive changes in their daily life in terms of living standards and, more importantly perhaps, the basic freedom of choice. He has lifted scores of restrictions that were solid features of life for the Syrians for decades. He has also initiated a series of economic reforms that would hopefully lead to better opportunities for his people.

Assad has charted a course starting with ensuring that his reforms do make a positive impact on people's life and then going on to introduce political reforms. He wants to prove it to his people that he could deliver what he promises. He has realised that only then he could hope for an absolute and unquestionable popular endorsement as the political leader of the country.

The US should accept the sequence and pace of events rather than trying to demand an overnight transformation of a political system that has existed for decades. What is it that the US wants in Syria? A French-style revolution?

Iran is a different kettle of fish altogether. For a majority of Iranians — Shiites — politics and religion go together and thus the Iranian political system does not conform to what Washington might see as ideal. The US is barking up the wrong tree by insisting on Iran having democracy of a style and shape that is acceptable to Washington. What the US wants in Iran is a sweeping change in a belief and conviction based on faith. How could that be acceptable to the Iranians? There might or might not be problems with the Iranian-style of democracy and governance, but it is the Iranians to decide what reforms they would like to accept. The US, or anyone else for that matter, has no business to dictate terms for change in any society except of course the Americans themselves (Let us not forget the resounding allegations within the US that the last presidential elections were rigged in some states. We don't recollect Rice talking about that either. Can't she do something about addressing those charges?).

Rice spoke about the people's freedom of choice. Surely, such a noble approach should be welcome to forces which are seeking changes in the Arab World.

However, we see a paradox here.

For starters, let us see how many opposition leaders — wherever they have been clearly identified — opted to join their voices to the American effort. Well, practically none.

Egypt's powerful Muslim Brotherhood, which could easily win elections if it is allowed to run as a political party and field candidates — hit the nail on the head by dismissing Rice's visit.

"We know that the US administration is not a benevolent organisation or a charity," said Mohammed Habib of the Brotherhood. "Its interests and agenda are not those of the Egyptian people."

Even the Kefaya (Enough) movement, the most active group in Egypt seeking reforms, turned down an invitation to meet Rice.

In principle, few in the Arab World dispute that the region needs reform. The Arabs agree with the US that ordinary people should have a direct role and say in the running of their affairs, but that is where the agreement stops. The Arabs are suspicious of the American agenda in the Middle East. They are aware of the American record while dealing with human rights and democracy. They know that democracy means little to the US when compared with what it considers as its strategic interests. That the US is driving for reforms in certain countries in itself is suspect because it is no coincidence that those countries happen to be hurdles in the American quest to achieve its strategic goals and serve its priorities where a genuine desire for democracy is far down the list.