PV Vivekanand

AMID TALK of Iraq being the next target in the US-led war against international terrorism, Washington is trapped between the need to consolidate its alliances in the effort by revealing more of its findings against Osama Bin Laden and his Al Qaeda network and fears that its intelligence sources would be compromised in the process.

The equation is quite clear: The military offensive against Afghanistan has brought out seething Arab and Muslim anger and frustration not only over the bombings against that country but also over the US insistence that it would not reveal the evidence it has against Bin Laden and Al Qaeda at this stage.

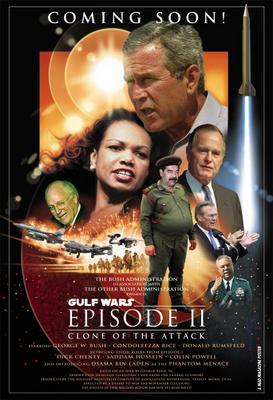

It is a dead certainty that the US would initiate military action against Iraq with the goal of ousting Saddam Hussein — on whatever pretexts — and installing an American-friendly regime in Baghdad.

The Arab sentiments would only be inflamed if the US were to maintain its insistence on secrecy and confidentiality of evidence in the Sept.11 case but go ahead with a military offensive against Iraq. That course of an event would lead to security and instability of some Arab governments which are half-hearted members of the US-led coalition against terrorism.

Equally enraging Arabs and Muslims is the pointed silence that Washington is maintaining over their demands that Israel, which has consistently defied UN resolutions and international legitimacy and is continuing brutal military assaults against the Palestinians, be treated as terrorist state.

While the logical course is to present the operative parts of the evidence for public consumption and satisfy the Arab and Muslim streets of the strength of its case, Washington might simply be unable to do so since it would compromise the sensitive intelligence sources that provided the clinching proof.

The main evidence against Bin Laden released to the public at this point is the money trail – cash transfers, credit cards and bank accounts that link some of the alleged hijackers in the Sept. 11 kamikaze attacks and known Bin Laden associates as well as common features in the assault against the New York and Washington landmarks and earlier attacks attributed to Al Qaeda.

Other elements of the US case link the suspected hijackers to the attacks themselves.

Washington has shared part of its findings with its European allies and Egypt and Saudi Arabia, two of its key Arab allies. But other partners in the coalition are demanding that they too be privvy to the evidence.

International experts and analysts say that a feud is raging between political strategists and intelligence agencies in Washington over how much information the US could afford to offer to its allies on a confidential basis and how much could be released for public consumption.

While the strategists argue that satisying the Arabs and Muslims at large is an integral part of strengthening their governments' support for the war against terrorism, intelligence agencies counter by pointing out that it would be too damaging for their investigations at this point.

Beyond that argument is the fear that the recipient governments would run the data through their intelligence networks and this would led to compromising the sources from where the US had gained the informaton.

The issue has assumed graver proportions with the US formally notifying the United Nations on Monday that it might target other countries in the war against terrorism and senior Bush administration officials mentioning Iraq as a potential target.

Given that there is only flimsy references to an alleged Iraqi role in the Sept. 11 attacks made available to the public at large, any assault on beleaguered Iraq would only inflame Arab and Muslim anger and frustration, and this could pose serious threats to the security and stabilty of their regimes.

Baghdad has vehemently denied suggestions that it had a role in the Sept.11 attacks based on reports of an alleged meeting between Mohammed Atta, a key suspect in the attacks, and an unidentitifed Iraqi diplomat somewhere in Europe sometime ago.

It has warned that the suggestions were a smokescreen for the US to settle political scores by destablising Iraq and indirectly topple the regime of Saddam Hussein — an objective the US failed to achieve in the 1991 Gulf war.