THE refurbished argument that the Taliban of

Afghanistan have gone "back" into producing opium

since the Sept. 11 attacks not only lacks logic and

sense, but also reflects a surprising lack of Western

understanding of the mindset of the rulers in power in

Kabul.

If anything, the US approach to the issue is

contradictory and murky. For one thing, many US

officials accuse the Taliban of growing drugs to

finance itself while the UN agency fighting narcotics

around the world has certified that the Taliban not

only ordered a total end of poppy production in the

country in early 2000 but also enforced it to the

letter.

At the same time, the US has no reluctance to deal

with the Taliban's foes, the Northern Alliance, which

the UN agency says survives on drugs produced outside

Taliban-controlled areas.

According to the January 2000 Taliban edict, issued

by none other than its spiritual leader Mullah Omar

Mohammed, growing, dealing, and using drugs is

"un-Islamic," and hence the ban.

The US, which is the hardest hit country by the menace

posed by narcotics, grudgingly admitted a few months

after the edict was issued that the Taliban were

indeed enforcing the ban, but the Northern Alliance

was continuing the trade.

Today, when the US suddenly found the Taliban as its

immediate enemy in its war against terrorism, open

occusations are levelled that the ruling Afghan

militia has resumed opium production and is posing an

additional threat to the international community in

addition to its support for terrorism.

Quite predictably, little is said about the proven

record of the Northern Ailliance in using narcotics as

one of its mainstay means of incomes and about the

newfound partnership the US has forged with the group

or groups that make up the opposition to the Taliban

in the country.

What is missing here is an American understanding that

the Taiban, despite all what the West sees as their

vagaries and support for terrorism, see themselves as

puritan sect based on the noblest of noble principles

and are committed to what they believe in. Of course,

what they see as noble might not be seen so by others.

But that does not have any bearing on the group's

strong belief in what it is doing.

As such, Mullah Omar's ban on opium production was not

just a bolt out of the blue, but a decision taken in

view of Islamic principles, and it is highly unlikely

that he would go back on that ban simply because it

suits him to hit back on the world community and earn

money in the bargain by resuming the drug trade. An

argument to the contrary reflects nothing but the

gaping hole in American understanding of the Taliban

in general.

Indeed, it is of course quite possible that the US and

its strategists have understood the reality but do not

want to acknowledge it because it would be against US

interests to even hint that the Taliban are living by

certain principles, flawed as they might be as they

appear to the West.

That is not to say that the way of life practised by

the Taliban is perfect or impure, conservative,

militant, hardline, moderate or liberal. That is for

religious scholars to decide. But it is important here

to understand the group's has an unflinching way of

thinking and would not deviate from that as a

political strategy.

What the US and the rest of the international

community fail to realise is that the way of life the

Taliban have chosen for themselves — right or wrong,

good or bad, fanatic or moderate — is not a strategy.

It would not be an exaggeration to say that the way of

life that the Taliban have adopted is as dear to the

movement as non-violence was the way of life for

Mahatma Gandhi.

Probably, the ongoing crisis might unravel itself if

the US were to understand this crucial truth and act

accordingly. Or is it too late?

Thursday, October 25, 2001

Saturday, October 20, 2001

Can Bush 'get' Bin Laden

Almost two weeks into the US-led military assault

against Afghanistan, the key question many people are

asking is: Will George Bush get Osama Bin Laden? Will

Bin Laden be caught alive? Or will he manage to slip

away?

Judging from whatever little has been disclosed by the

US of its military strategy, it is abundantly clear

that without deploying a sizeable ground force

supported by massive and close air cover, the US-led

coalition would not be able to do much in real terms.

And the risk of battle-hardened Taliban fighters

engaging the invaders in the rough terrains of the

Afghan mountains is pretty high.

It is often heard these days that Afghanistan has

always made things difficult for invaders, starting

with Alexander the Great to British forces at the peak

of the colonial days to the Red Army in the 80s. The

immediate counterpoint is also heard: None of those

invaders had the hi-tech military might to back them.

Put in simple terms, the US has the firepower to

demolish mountains in their entirety if they stood in

the way. That is a luxury that none of the previous

invaders had.

Indeed, with the raid carried out by Special Forces

near Kandahar on Saturday (as Friday night depending

on which part of the world you are in), the US has

launched the riskiest part — but also potentially

decisive stage — of its military action against

Afghanistan in the war against terrorism.

Breaking away from 12 days of aerial bombings and

missile attacks, the US sent over 100 Army Rangers —

highly trained soldiers from the Special Forces — for

the operation and pulled them out safely after they

accomplished whatever they went in for. Command

centres would have heaved a big sigh when it was

confirmed that the operation was over without any

American casualties.

The actual impact of the raid apart, the operation was

also important in symbolism: US President George W

Bush was tellng his allies and foes alike that he was

not bluffing when he said he was determined to see

through the war against terrorism and ready for the

risk it carries in terms of American casualties.

Seen against Bush's firm pledges and obvious

determination, it is foregone conclusion that he has

already ordered his commanders to do what it takes to

achieve the US objective: Get Bin Laden dead or alive.

Now we also hear that the action against Afghanistan

could stretch for months, even until April of May.

Politics of the equation apart (dwindling Arab, Muslim

and international support in the event of a protracted

conflict), the US seems confident of its ability to

sustain the action. However, it still does not

necessarily mean Bush would get Bin Laden.

Bush's ultimate glory would indeed be television

footage of a hand-cuffed and rejected looking Bin

Laden escorted into a US helicopter by US soldiers for

trial in the US. But it seems like his ultimate,

unrealisable dream too. For, those who have known Bin

Laden in Afghanistan swear on their soul that the

number one enemy of the US would not be taken alive.

They say that Bin Laden, who rejects suicide in line

with his Islamist beliefs, always keeps one guard

close to him with a loaded gun and strict

instructions: Shoot and kill me if capture becomes

inevitable.

against Afghanistan, the key question many people are

asking is: Will George Bush get Osama Bin Laden? Will

Bin Laden be caught alive? Or will he manage to slip

away?

Judging from whatever little has been disclosed by the

US of its military strategy, it is abundantly clear

that without deploying a sizeable ground force

supported by massive and close air cover, the US-led

coalition would not be able to do much in real terms.

And the risk of battle-hardened Taliban fighters

engaging the invaders in the rough terrains of the

Afghan mountains is pretty high.

It is often heard these days that Afghanistan has

always made things difficult for invaders, starting

with Alexander the Great to British forces at the peak

of the colonial days to the Red Army in the 80s. The

immediate counterpoint is also heard: None of those

invaders had the hi-tech military might to back them.

Put in simple terms, the US has the firepower to

demolish mountains in their entirety if they stood in

the way. That is a luxury that none of the previous

invaders had.

Indeed, with the raid carried out by Special Forces

near Kandahar on Saturday (as Friday night depending

on which part of the world you are in), the US has

launched the riskiest part — but also potentially

decisive stage — of its military action against

Afghanistan in the war against terrorism.

Breaking away from 12 days of aerial bombings and

missile attacks, the US sent over 100 Army Rangers —

highly trained soldiers from the Special Forces — for

the operation and pulled them out safely after they

accomplished whatever they went in for. Command

centres would have heaved a big sigh when it was

confirmed that the operation was over without any

American casualties.

The actual impact of the raid apart, the operation was

also important in symbolism: US President George W

Bush was tellng his allies and foes alike that he was

not bluffing when he said he was determined to see

through the war against terrorism and ready for the

risk it carries in terms of American casualties.

Seen against Bush's firm pledges and obvious

determination, it is foregone conclusion that he has

already ordered his commanders to do what it takes to

achieve the US objective: Get Bin Laden dead or alive.

Now we also hear that the action against Afghanistan

could stretch for months, even until April of May.

Politics of the equation apart (dwindling Arab, Muslim

and international support in the event of a protracted

conflict), the US seems confident of its ability to

sustain the action. However, it still does not

necessarily mean Bush would get Bin Laden.

Bush's ultimate glory would indeed be television

footage of a hand-cuffed and rejected looking Bin

Laden escorted into a US helicopter by US soldiers for

trial in the US. But it seems like his ultimate,

unrealisable dream too. For, those who have known Bin

Laden in Afghanistan swear on their soul that the

number one enemy of the US would not be taken alive.

They say that Bin Laden, who rejects suicide in line

with his Islamist beliefs, always keeps one guard

close to him with a loaded gun and strict

instructions: Shoot and kill me if capture becomes

inevitable.

Sharon targets Arafat

By PV Vivekanand

IF WE were to take Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon seriously, then the worst development in the Israeli-Palestinian equation is not the killing of Israeli minister Rehavam Zeevi but Sharon's assertion that the era of Yasser Arafat was over.

If anything, Sharon's declaration and dispatch of several ministers to convince Washington that Arafat was no longer a viable partner for peace reeks of Israel's well-known arrogance and contemptuous treatment of the Palestinians.

Equally sinister is Sharon's "warning" of an impending war: “Arafat has seven days to impose absolute quiet in the (occupied) territories. Ifnot, we will go to war against him. As far as I am concerned, the era ofArafat is over.”

One wonders how far Israel is willing to go in Sharon's war. If the hawkish former general's record is anything to go by, then it would mean Israeli soldiers armed to the teeth and supported by heavy tanks, bombers and helicopters entering Palestinian towns and villages to "eliminate" every trace of resistance. Quite simply a re-enactment of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and of course the massacre of thousands in Sabra and Shattila.

But the Israeli premier is riding on false hopes if he believes that a change of guard at the leadership would make any difference to the Palestinians' determination to gain their legitimate rights and not to be dissuaded from adopting whatever means they have at their disposal to achieve that goal.

The worst mistake Israel ever made in the Middle East peace process was taking the Palestinian people for granted and assuming that the decades of brutal occupation have co-opted them into accepting that they were not a match to Israel's military might and, as such, they should be thankful to whatever Israel was willing to offer them.

Israel coerced Arafat into accepting the 1993 Oslo agreement by partly intimidating him with a scenario of Palestinian Islamists (like Hamas and allied groups) gaining strength and popularity in the occupied territories at the expense of the nationalists represented by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO).

Arafat was more than tempted to accept Oslo. He had found himself largely isolated in the Arab World as a result of the pro-Iraq position he had adopted during the Iraq-Kuwait crisis. So, the Oslo agreements represented his political salvation, another element that Israel counted for itself in the bargain.

Since then, regardless of whoever was in power, Israel expected Arafat to act as its proxy policeman in the occupied territories by keeping the Palestinian people in check and containing armed resistance.

To a large extent, it worked for some time. A majority of the Palestinians were indeed tired and frustrated over what they saw as the impossibility of the situation and were jubiliant when the Oslo agreement was signed. They were willing to give peace a chance.

Many actually expected a total Israeli withdrawal from most of the land the Jewish state occupied in the 1967 war and Arab East Jerusalem be named the capital of an independent Palestinian state under some compromise arrangement even it meant giving up part of the Arab identity of the city. For them it was largely a matter of technicalities that needed to be addressed in the process.

However, problems started cropping up when Israel started showing its real colours, and soon it became clear that the Israeli scenario under the Oslo agreement would involve heavy territorial compromises and political limitations for the Palestinians. In the meantime, Israel sought to legitimise itself in the region through Arab recognition.

The signs of the Israeli approach manifested themselves from day one.

We recall distinctly Israel's refusal to hand over a map of the Palestinian territory showing the potential shape of a Palestinian entity as promised at the sighing in Cairo in June 1994 of the first "implementation" deal as the first phase of the Oslo accord.

Arafat refused to sign the agreement, and it took a lot of persuasion and promises by the US that no matter what the inalienable rights of the Palestinians would be respected in the "final status negotiations" before he signed the deal. After all, UN Security Council resolutions were the basis for a final agreement, he was assured.

Similar situations were re-enacted at every stage since then, and everytime it was the Palestinians who had to give up something.

The Israeli strategy was clear: It began negotiations on every phase of implementing the Oslo agreement by imposing tough demands, and the Palestinians put up resistance. Obviously the deadlock had to be broken and the mediator, the US, was brought in inevitably. The end result was simple: Agreements were reached, but they involved Palestinian compromises more than Israeli "concessions." If anything, on a scale of 1-10 (10 being the full realisation of Palestinian rights), Israel "maganimously" gave up 2 and the Palestinians surrendered 8. And when it came to actual implemenation, Israel fell short of its obligation to give up 2 and the Palestinians were asked to absorb that loss.

The Palestiniain experience was repeated at every stage of the negotiations.

The shifting political powers in Israel since 1996 had had their bearing on the negotiations, but not in real terms since the bipartisan Israeli objective was clear; the Palestinians have to remain under Israel's control in whatever form and shape, with limited political and territorial freedom. Furthermore, Israel always sought to retain the West Bank and Gaza as a captive market for its products (the annual Israeli "exports" to the Palestinian territories are around $2 billon).

The dreams of an independent Palestinian state with Arab East Jerusalem as its capital suffered a serious setback in the summer of 2000 when the then Israeli prime minister, Ehud Barak, made it clear that Israel had no intention ever to respect the Arab and Islamic identity of the Holy City by returning it to the Palestinians.

The three main elements that foiled a peace accord being worked out at Camp David in August last year were:

— Israel's refusal to respect the Palestinian rights to Arab East Jerusalem.

— Israel's rejection of the "right of return" of upto four million Palestinian refugees.

— Israel's insistence on keeping territorial control over large chunks of West Bank land that would have deprived the Palestinians of physical continuity that is vital for an independent state.

The deadlock at Camp David led to a sudden surge of Palestinian frustration, and Sharon's infamous visit to Al Aqsa in September as a declaration of Israel's determination not to give up Arab East Jerusalem broke the proverbial last straw for the Palestinians. The Intifada — the anti-occupation revolt that was part of the reason that prompted Israel to join the peace process in 1991 — was relaunched with increased intensity.

The writing went up on the wall when Sharon was elected prime minister early this year that the Palestinian hopes were dealt another serious blow, for his record of hatred for anything Arab was well known; so was his campaign to evict all the Palestinian across the River Jordan.

We have clearly seen what happened since Sharon's election. Israel stepped up the intensity of its military bruality against the Palestinians and the cycle of violence continued.

Today, international condemnation makes little difference to Israel when its sends its hi-tech fighter planes, helicopter gunships and tanks into war-like action against the residents of the West Bank and Gaza.

Israel wasted no opportunity to discredit Yasser Arafat in front of his own people. Israeli leaders have made no secret of their conviction that Arafat was expected to carry out Israel's wishes against his own people.

Zeevi's killing was the natural result of Israel's actions. There would be more to come. Neither Arafat nor any other Palestinian leader would be able to check the manifestations of their people's fury and frustration against occupation.

Sharon's argument that Arafat is no longer a credible counterpart to discuss peace stems only from the Palestinian leader's refusal to mow down his own people. Washington should know better than to conveniently accept Sharon's argument. The consequences would be unpredictable.

IF WE were to take Israeli Prime Minister Ariel Sharon seriously, then the worst development in the Israeli-Palestinian equation is not the killing of Israeli minister Rehavam Zeevi but Sharon's assertion that the era of Yasser Arafat was over.

If anything, Sharon's declaration and dispatch of several ministers to convince Washington that Arafat was no longer a viable partner for peace reeks of Israel's well-known arrogance and contemptuous treatment of the Palestinians.

Equally sinister is Sharon's "warning" of an impending war: “Arafat has seven days to impose absolute quiet in the (occupied) territories. Ifnot, we will go to war against him. As far as I am concerned, the era ofArafat is over.”

One wonders how far Israel is willing to go in Sharon's war. If the hawkish former general's record is anything to go by, then it would mean Israeli soldiers armed to the teeth and supported by heavy tanks, bombers and helicopters entering Palestinian towns and villages to "eliminate" every trace of resistance. Quite simply a re-enactment of the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon and of course the massacre of thousands in Sabra and Shattila.

But the Israeli premier is riding on false hopes if he believes that a change of guard at the leadership would make any difference to the Palestinians' determination to gain their legitimate rights and not to be dissuaded from adopting whatever means they have at their disposal to achieve that goal.

The worst mistake Israel ever made in the Middle East peace process was taking the Palestinian people for granted and assuming that the decades of brutal occupation have co-opted them into accepting that they were not a match to Israel's military might and, as such, they should be thankful to whatever Israel was willing to offer them.

Israel coerced Arafat into accepting the 1993 Oslo agreement by partly intimidating him with a scenario of Palestinian Islamists (like Hamas and allied groups) gaining strength and popularity in the occupied territories at the expense of the nationalists represented by the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO).

Arafat was more than tempted to accept Oslo. He had found himself largely isolated in the Arab World as a result of the pro-Iraq position he had adopted during the Iraq-Kuwait crisis. So, the Oslo agreements represented his political salvation, another element that Israel counted for itself in the bargain.

Since then, regardless of whoever was in power, Israel expected Arafat to act as its proxy policeman in the occupied territories by keeping the Palestinian people in check and containing armed resistance.

To a large extent, it worked for some time. A majority of the Palestinians were indeed tired and frustrated over what they saw as the impossibility of the situation and were jubiliant when the Oslo agreement was signed. They were willing to give peace a chance.

Many actually expected a total Israeli withdrawal from most of the land the Jewish state occupied in the 1967 war and Arab East Jerusalem be named the capital of an independent Palestinian state under some compromise arrangement even it meant giving up part of the Arab identity of the city. For them it was largely a matter of technicalities that needed to be addressed in the process.

However, problems started cropping up when Israel started showing its real colours, and soon it became clear that the Israeli scenario under the Oslo agreement would involve heavy territorial compromises and political limitations for the Palestinians. In the meantime, Israel sought to legitimise itself in the region through Arab recognition.

The signs of the Israeli approach manifested themselves from day one.

We recall distinctly Israel's refusal to hand over a map of the Palestinian territory showing the potential shape of a Palestinian entity as promised at the sighing in Cairo in June 1994 of the first "implementation" deal as the first phase of the Oslo accord.

Arafat refused to sign the agreement, and it took a lot of persuasion and promises by the US that no matter what the inalienable rights of the Palestinians would be respected in the "final status negotiations" before he signed the deal. After all, UN Security Council resolutions were the basis for a final agreement, he was assured.

Similar situations were re-enacted at every stage since then, and everytime it was the Palestinians who had to give up something.

The Israeli strategy was clear: It began negotiations on every phase of implementing the Oslo agreement by imposing tough demands, and the Palestinians put up resistance. Obviously the deadlock had to be broken and the mediator, the US, was brought in inevitably. The end result was simple: Agreements were reached, but they involved Palestinian compromises more than Israeli "concessions." If anything, on a scale of 1-10 (10 being the full realisation of Palestinian rights), Israel "maganimously" gave up 2 and the Palestinians surrendered 8. And when it came to actual implemenation, Israel fell short of its obligation to give up 2 and the Palestinians were asked to absorb that loss.

The Palestiniain experience was repeated at every stage of the negotiations.

The shifting political powers in Israel since 1996 had had their bearing on the negotiations, but not in real terms since the bipartisan Israeli objective was clear; the Palestinians have to remain under Israel's control in whatever form and shape, with limited political and territorial freedom. Furthermore, Israel always sought to retain the West Bank and Gaza as a captive market for its products (the annual Israeli "exports" to the Palestinian territories are around $2 billon).

The dreams of an independent Palestinian state with Arab East Jerusalem as its capital suffered a serious setback in the summer of 2000 when the then Israeli prime minister, Ehud Barak, made it clear that Israel had no intention ever to respect the Arab and Islamic identity of the Holy City by returning it to the Palestinians.

The three main elements that foiled a peace accord being worked out at Camp David in August last year were:

— Israel's refusal to respect the Palestinian rights to Arab East Jerusalem.

— Israel's rejection of the "right of return" of upto four million Palestinian refugees.

— Israel's insistence on keeping territorial control over large chunks of West Bank land that would have deprived the Palestinians of physical continuity that is vital for an independent state.

The deadlock at Camp David led to a sudden surge of Palestinian frustration, and Sharon's infamous visit to Al Aqsa in September as a declaration of Israel's determination not to give up Arab East Jerusalem broke the proverbial last straw for the Palestinians. The Intifada — the anti-occupation revolt that was part of the reason that prompted Israel to join the peace process in 1991 — was relaunched with increased intensity.

The writing went up on the wall when Sharon was elected prime minister early this year that the Palestinian hopes were dealt another serious blow, for his record of hatred for anything Arab was well known; so was his campaign to evict all the Palestinian across the River Jordan.

We have clearly seen what happened since Sharon's election. Israel stepped up the intensity of its military bruality against the Palestinians and the cycle of violence continued.

Today, international condemnation makes little difference to Israel when its sends its hi-tech fighter planes, helicopter gunships and tanks into war-like action against the residents of the West Bank and Gaza.

Israel wasted no opportunity to discredit Yasser Arafat in front of his own people. Israeli leaders have made no secret of their conviction that Arafat was expected to carry out Israel's wishes against his own people.

Zeevi's killing was the natural result of Israel's actions. There would be more to come. Neither Arafat nor any other Palestinian leader would be able to check the manifestations of their people's fury and frustration against occupation.

Sharon's argument that Arafat is no longer a credible counterpart to discuss peace stems only from the Palestinian leader's refusal to mow down his own people. Washington should know better than to conveniently accept Sharon's argument. The consequences would be unpredictable.

Monday, October 15, 2001

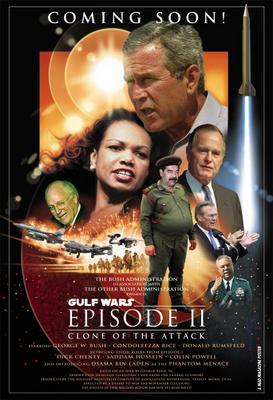

Iraq next target

PV Vivekanand

AMID TALK of Iraq being the next target in the US-led war against international terrorism, Washington is trapped between the need to consolidate its alliances in the effort by revealing more of its findings against Osama Bin Laden and his Al Qaeda network and fears that its intelligence sources would be compromised in the process.

The equation is quite clear: The military offensive against Afghanistan has brought out seething Arab and Muslim anger and frustration not only over the bombings against that country but also over the US insistence that it would not reveal the evidence it has against Bin Laden and Al Qaeda at this stage.

It is a dead certainty that the US would initiate military action against Iraq with the goal of ousting Saddam Hussein — on whatever pretexts — and installing an American-friendly regime in Baghdad.

The Arab sentiments would only be inflamed if the US were to maintain its insistence on secrecy and confidentiality of evidence in the Sept.11 case but go ahead with a military offensive against Iraq. That course of an event would lead to security and instability of some Arab governments which are half-hearted members of the US-led coalition against terrorism.

Equally enraging Arabs and Muslims is the pointed silence that Washington is maintaining over their demands that Israel, which has consistently defied UN resolutions and international legitimacy and is continuing brutal military assaults against the Palestinians, be treated as terrorist state.

While the logical course is to present the operative parts of the evidence for public consumption and satisfy the Arab and Muslim streets of the strength of its case, Washington might simply be unable to do so since it would compromise the sensitive intelligence sources that provided the clinching proof.

The main evidence against Bin Laden released to the public at this point is the money trail – cash transfers, credit cards and bank accounts that link some of the alleged hijackers in the Sept. 11 kamikaze attacks and known Bin Laden associates as well as common features in the assault against the New York and Washington landmarks and earlier attacks attributed to Al Qaeda.

Other elements of the US case link the suspected hijackers to the attacks themselves.

Washington has shared part of its findings with its European allies and Egypt and Saudi Arabia, two of its key Arab allies. But other partners in the coalition are demanding that they too be privvy to the evidence.

International experts and analysts say that a feud is raging between political strategists and intelligence agencies in Washington over how much information the US could afford to offer to its allies on a confidential basis and how much could be released for public consumption.

While the strategists argue that satisying the Arabs and Muslims at large is an integral part of strengthening their governments' support for the war against terrorism, intelligence agencies counter by pointing out that it would be too damaging for their investigations at this point.

Beyond that argument is the fear that the recipient governments would run the data through their intelligence networks and this would led to compromising the sources from where the US had gained the informaton.

The issue has assumed graver proportions with the US formally notifying the United Nations on Monday that it might target other countries in the war against terrorism and senior Bush administration officials mentioning Iraq as a potential target.

Given that there is only flimsy references to an alleged Iraqi role in the Sept. 11 attacks made available to the public at large, any assault on beleaguered Iraq would only inflame Arab and Muslim anger and frustration, and this could pose serious threats to the security and stabilty of their regimes.

Baghdad has vehemently denied suggestions that it had a role in the Sept.11 attacks based on reports of an alleged meeting between Mohammed Atta, a key suspect in the attacks, and an unidentitifed Iraqi diplomat somewhere in Europe sometime ago.

It has warned that the suggestions were a smokescreen for the US to settle political scores by destablising Iraq and indirectly topple the regime of Saddam Hussein — an objective the US failed to achieve in the 1991 Gulf war.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)